SourceThe Infinite Game. New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2019. ISBN 9780735213500, Chapter 2 - What a Just Cause Is - For something — affirmative and optimistic

A Just Cause is something we stand for and believe in, not something we oppose. Leaders can rally people against something quite easily. They can whip them into a frenzy, even. For our emotions can run hot when we are angry or afraid. Being for something, in contrast, is about feeling inspired. Being for ignites the human spirit and fills us with hope and optimism. Being against is about vilifying, demonizing or rejecting. Being for is about inviting all to join in common cause. Being against focuses our attention on the things we can see in order to elicit reactions. Being for focuses our attention on the unbuilt future in order to spark our imaginations.

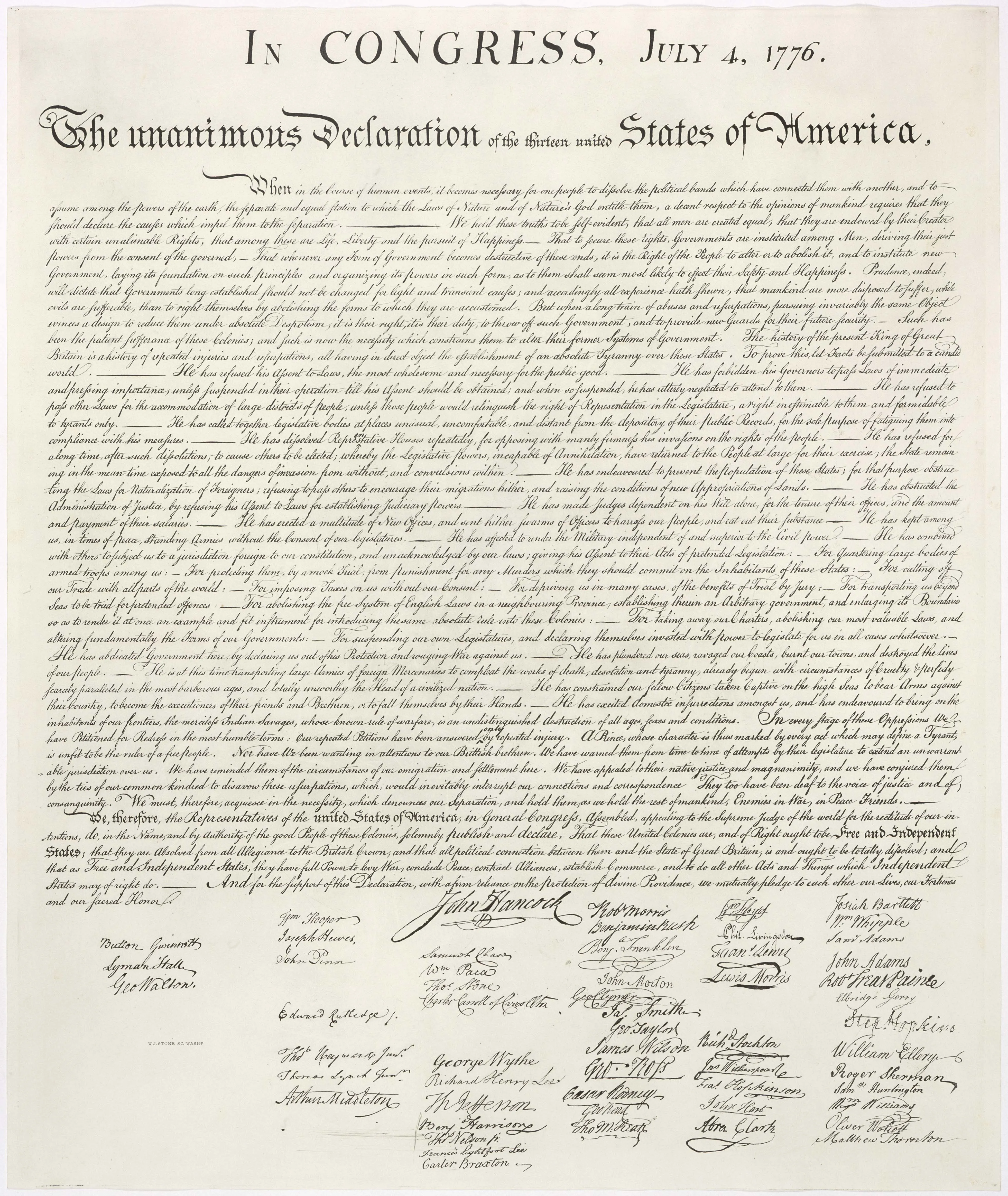

Imagine if instead of fighting against poverty, for example, we fought for the right of every human to provide for their own family. The first creates a common enemy, something we are against. It sets up the Cause as if it is “winnable,” i.e., a finite game. It leads us to believe that we can defeat poverty once and for all. The second gives us a cause to advance. The impact of the two perspectives is more than semantics. It affects how we view the problem/vision that affects our ideas on how we can contribute. Where the first offers us a problem to solve, the second offers a vision of possibility, dignity and empowerment. We are not inspired to “reduce” poverty, we are inspired to “grow” the number of people who are able to provide for themselves and their families. Being for or being against is a subtle but profound difference that the writers of the Declaration of Independence intuitively understood.

Those who led America toward independence stood against Great Britain in the short term. Indeed the American colonists were deeply offended by how they were treated by England. Over 60 percent of the Declaration of Independence is spent laying out specific grievances against the king. However, the Cause they were fighting for was the true source of lasting inspiration, and in the Declaration of Independence it came before anything else. It is the first idea we read in the document. It sets the context for the rest of the Declaration and the direction for moving forward. It is the ideal to which we personally relate and that we have easily committed to memory. Few Americans, except for scholars and the most zealous of history buffs, can rattle off even one of the complaints listed later in the document, things like: “He has endeavored to prevent the Population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.” In contrast, most Americans can recite with ease “all men are created equal” and can usually rattle off the three tenets of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” These words are indelibly marked on the cultural psyche. Invoked by patriots and politicians alike, they remind Americans of who we strive to be and the ideals upon which our nation was founded. They tell us what we stand for.